|

I finally have finished photos of the burl-stocked fowling piece available. These are shown in the Sample of Work tab. Additional views are also shown below. I would like to thank Anne Reese for these photos. I am happy that a buyer came forward at the Lake Cumberland show and the gun is sold. I enjoy this style and period of work, and would love to do more work like this in the future. If you have any questions, please ask.

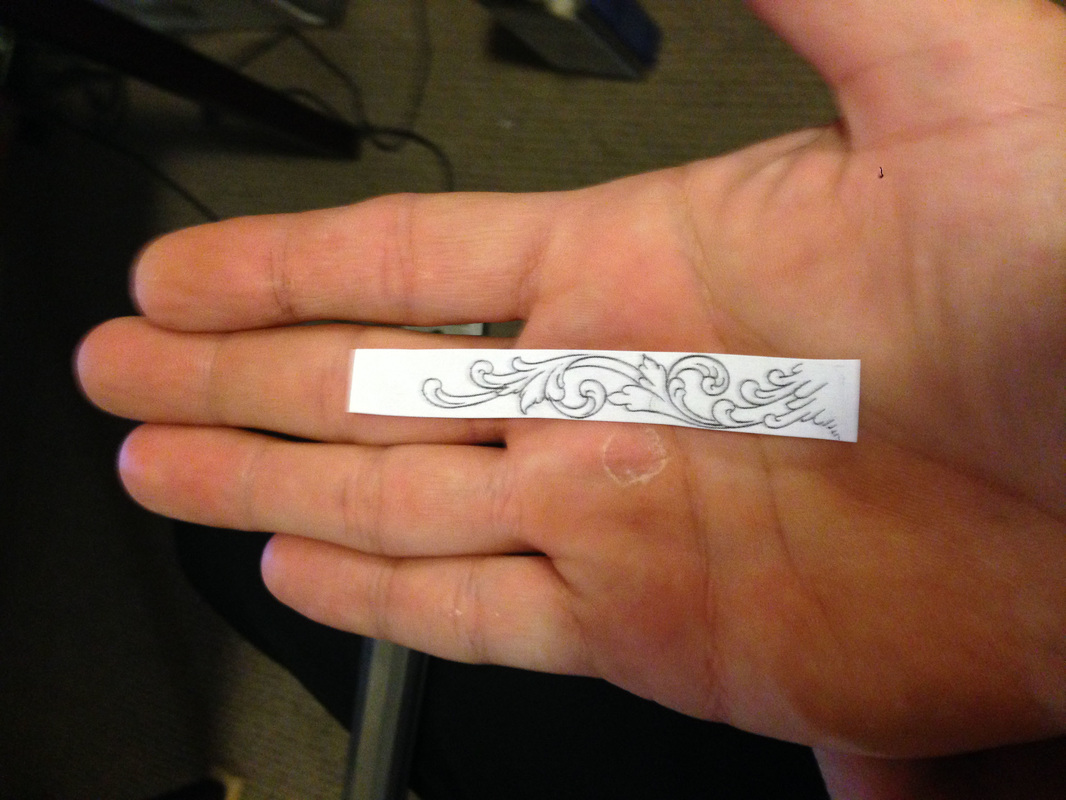

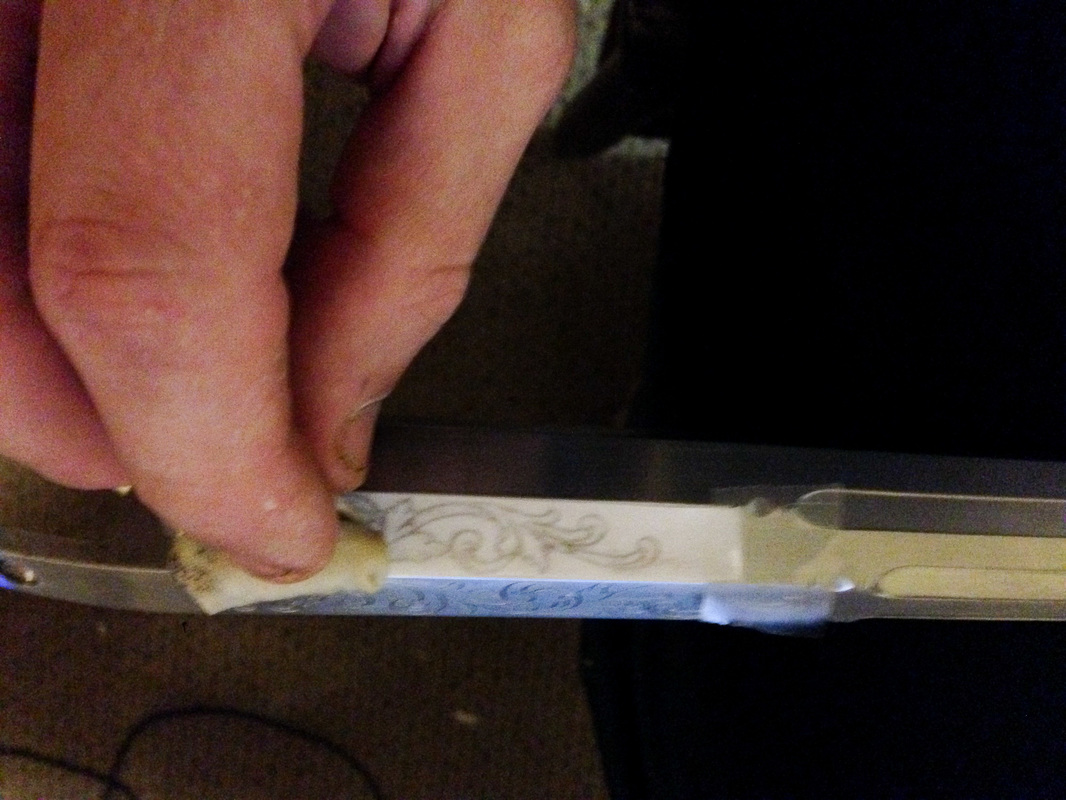

Photo Credits Anne Reese I'm happy to announce that I've completed the fowling piece I have been working on. I apologize for not posting my progress sooner. Along with some other projects, I've been working for some time engraving this project. This gun is by far the most extensively engraved piece I've made to date. Engraving certainly isn't an easy process and this project has been a learning experience. So, I'd like to talk a bit about engraving. This, of course, is not meant for the professional engraver, but rather those like myself who do a lot of different work and are continually trying to improve. The following is a brief outline of the steps I use. First a design must be established. It's always been problematic for me to design directly on the workpiece. For simple forms this has worked out okay, but as things become more complicated, it's become much more difficult. A very good solution is to design on paper and then transfer this to the workpiece. The design can be drawn much larger than what is desired to be engraved and then resized using a computer and printer prior to transfer. This allows details to be established more easily. When designing on paper, the primary focus is to establish appealing forms and design outlines. I typically do not include shading at this stage. In order to perform a transfer, the design is printed using a laser printer, placed face down on the work piece and then acetone is used to soften the ink and then allow it to attach to the metal. There are many methods to perform this process, but this method has worked adequately for me. After the design is transferred, the outline is engraved and established. On hard metals such as iron, steel and even brass, engraving methods are generally limited to hammer and chisel or power assist engraving units. I learned hammer and chisel engraving many years ago, so I find it pretty comfortable. I own a Lindsay, palm control, air graver, but am less confident with it. In fact, I rarely use it and may end up selling it. If your interested, let me know. A key aspect to successful engraving is proper and consistent graver sharpening. I would suggest using any of the good fixtures available from Steve Lindsay or GRS. During engraving, care is taken to create smooth, flowing curves which accurately represent the design previously worked out. Engraving can vary in weight to accentuate the forms being created. In practice, multiple lines, often varying in thickness are cut to darken particular areas. As lines are placed closer together the result is an increasing degree of darkness. With skill, very beautiful and appealing designs can result. A final and optional step in engraving is darken the cuts. I generally use a chemical which will oxidize the metal. By oxidizing the entire piece and then polishing it from the surface, increased contrast will result. As I mentioned, engraving isn't easy, but with hard work and determination good things can happen. I will share finished photos of this gun relatively soon. It is of course available and those who have expressed interest will be hearing from me soon. I'm pleased with the results, and think it's some of my best work. I will be showing this fowling piece at the upcoming Lake Cumberland Show on Feburary 6th thru 8th. In addition I'll be bringing some examples of the jewelry Katherine and I are making. Hope to see you there! Next, the design must be shaded to create depth and interest. I find this to be the most difficult aspect of engraving. Drawing shade cuts on an enlarged and printed version of the design can be helpful in understanding how to shade and create the desired effect.

Hey there everyone. Time for another post... In this segment, I'll show some of the steps used to make a steel thumb piece for the fowling piece I've been working on. Steel hardware with carved relief can be produced by forming the part and chiseling or by investment casting. Both methods have their merits and drawbacks. In the case of the thumb piece being discussed, I chose to carve a master and investment cast the steel part. After casting, it was cleaned up with gravers, rifflers and polishing stones. The master thumb piece was carved out of high density polyurethane modeling board. The stuff I used was sold under the name "Butter board". It carves well and is a pretty nice material to use.

The as-cast surface finish was pretty decent, but still required significant attention to clean up well. In this case I used a combination of riffler files and polishing stones. Gravers were used to add details not included in the casting. This isn't a fast process, but is required to make a cast piece look as good as it can and to emulate a chiseled piece. Finally the thumb piece was inlet into the stock. I realize this wasn't a highly detailed summary, so if you have any questions at all, don't hesitate to ask. I enjoy the feedback. I'd also like to thank everyone for the positive response concerning these blog posts. They take a bit of time and I always seem to be behind with my gun work, but I enjoy sharing a little bit of what I've been working on.

The burl stocked fowling piece will be completed soon. Basically some lock work and engraving left. I'd like to mention that I've built this as a "spec" piece and that it isn't sold. So if you should have an interest, let me know. I'm not certain what I will need for it at this point. I would like to make a final decision after the entire project is complete. It will be nice when it's done and move onto the next one! Thanks, Jim It's been a while since I've last posted here, so I wanted to take a little time to discuss some of what I've been working on recently. Barrel finishing isn't a huge job, or too complex, but something worth talking about. The barrel on the burl-stocked fowling piece project will be the focus of this discussion. This barrel can basically be described as a three stage, octagon to round barrel. The forward most section is round, the middle section is also round, but separated by wedding bands and the breech section is octagon with decorative file work. This is a barrel form typically seen on 17th century smoothbore guns. Modern barrels with round sections are produced by turning on a lathe. Done properly, this process efficiently produces relatively true round profiles, but also results in a finish with slight waves and imperfections. In order to smooth these out, the barrel must be filed or "struck". Striking a barrel generally refers to using a file length-wise over the barrel surface to create a more consistent surface. This process is especially important for barrels with "swamp" or curved profiles since these shapes are typically comprised of several straight sections blended together. I have found a Vixen file to be useful for this process. A friend has also suggested a 6-8" section of low angle lathe file to work very well. In practice the file is held against the barrel in a lengthwise fashion and pushed across this surface. This process is repeated around the barrel perimeter in order to accommodate the round cross section. The file will contact the high areas and cut them down to create a relatively smooth contour. After striking the barrel, I use a mill file and draw file the surface. This improves the finish. Draw filing is basically a process where a mill file is held more or less perpendicular to the barrel axis. It can be pushed or pulled and results in shavings produced from a shearing cut. Finishes from this technique are typically pretty good. The next step is to further smooth the surface using abrasive paper wrapped around a flexible backer material. I find finishing to 320 grit sufficient for a surface left bright. Finally, working the surface with Scotch-Brite abrasive pads evens things out a bit and improves the finish. A few notes about striking a barrel... A round barrel left bright will show even the tiniest waves or imperfection from the turning process, so striking is very important. On barrels with significant profile, a thinner file can be used so it will bend to shape. Striking is also useful for octagon barrels where straight segments don't blend well. As can be seen, the breech section of the barrel shown has a section where the corners of the octagon are removed, creating the appearance of a 16 sided region. Again, this is typically seen on 17th century work. A front sight was added to this barrel by cutting a recess and slightly swaging material around the sight, locking it in place. In practice the sight is slightly upset on the bottom surface allowing for a good mechanical joint. This fowling piece barrel is relatively thin, but this process can still be used with care. In this case the sight is iron and the form was taken from a 17th century design by Andrew Dolep. As an aside, here's a final shot showing the sideplate for the burl-stocked gun. It's interesting that the serpentine sideplate first showed up in Paris around 1670 or so, but continued to see use on trade guns until the second half of the 19th century! By the very early 18th century, it had become out of fashion on most other work. Well, that's all for now. Lots of work to get done as always. Questions and comments are always welcomed.

Jim |

AuthorJim Kibler--maker of flintlock rifles. Archives

May 2019

Categories

All

|

Kibler's Longrifles

HoursM-F: 8am - 6pm

|

Telephone |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed