|

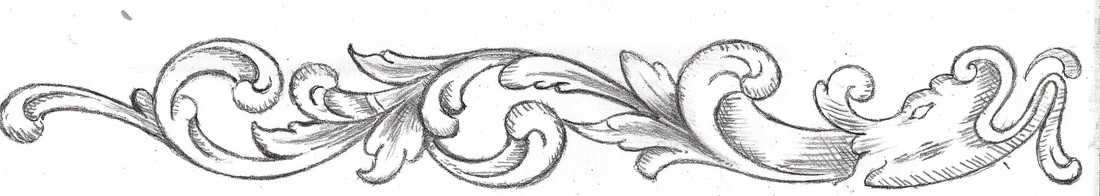

I'm happy to announce that I've completed the fowling piece I have been working on. I apologize for not posting my progress sooner. Along with some other projects, I've been working for some time engraving this project. This gun is by far the most extensively engraved piece I've made to date. Engraving certainly isn't an easy process and this project has been a learning experience. So, I'd like to talk a bit about engraving. This, of course, is not meant for the professional engraver, but rather those like myself who do a lot of different work and are continually trying to improve. The following is a brief outline of the steps I use. First a design must be established. It's always been problematic for me to design directly on the workpiece. For simple forms this has worked out okay, but as things become more complicated, it's become much more difficult. A very good solution is to design on paper and then transfer this to the workpiece. The design can be drawn much larger than what is desired to be engraved and then resized using a computer and printer prior to transfer. This allows details to be established more easily. When designing on paper, the primary focus is to establish appealing forms and design outlines. I typically do not include shading at this stage. In order to perform a transfer, the design is printed using a laser printer, placed face down on the work piece and then acetone is used to soften the ink and then allow it to attach to the metal. There are many methods to perform this process, but this method has worked adequately for me. After the design is transferred, the outline is engraved and established. On hard metals such as iron, steel and even brass, engraving methods are generally limited to hammer and chisel or power assist engraving units. I learned hammer and chisel engraving many years ago, so I find it pretty comfortable. I own a Lindsay, palm control, air graver, but am less confident with it. In fact, I rarely use it and may end up selling it. If your interested, let me know. A key aspect to successful engraving is proper and consistent graver sharpening. I would suggest using any of the good fixtures available from Steve Lindsay or GRS. During engraving, care is taken to create smooth, flowing curves which accurately represent the design previously worked out. Engraving can vary in weight to accentuate the forms being created. In practice, multiple lines, often varying in thickness are cut to darken particular areas. As lines are placed closer together the result is an increasing degree of darkness. With skill, very beautiful and appealing designs can result. A final and optional step in engraving is darken the cuts. I generally use a chemical which will oxidize the metal. By oxidizing the entire piece and then polishing it from the surface, increased contrast will result. As I mentioned, engraving isn't easy, but with hard work and determination good things can happen. I will share finished photos of this gun relatively soon. It is of course available and those who have expressed interest will be hearing from me soon. I'm pleased with the results, and think it's some of my best work. I will be showing this fowling piece at the upcoming Lake Cumberland Show on Feburary 6th thru 8th. In addition I'll be bringing some examples of the jewelry Katherine and I are making. Hope to see you there! Next, the design must be shaded to create depth and interest. I find this to be the most difficult aspect of engraving. Drawing shade cuts on an enlarged and printed version of the design can be helpful in understanding how to shade and create the desired effect.

Comments

For the last several days, I've been working on shaping and polishing hardware on the 17th century fowling piece introduced in the last post. Some of the hardware was copied from an original gun by Herman Bongarde of Dusseldorf, Germany and some is my own design created from masters I produced. In this segment, I will show some of the steps relating to finishing a cast guard with relief decoration. Filing and polishing standard hardware void of relief decoration is pretty standard fare and doesn't require a lot of special consideration. It of course requires filing and then polishing with successively finer abrasives. These abrasives can be in the form of paper, stones or loose particles. With relief work, the process becomes a bit more challenging. Background must be carefully worked with small files, stones or special purpose bent files or riflers. The first choice is always a standard file, but these will only access certain areas. If these aren't suitable, stones or special purpose tools must be used. After the background is cleaned up, attention is paid to the actual relief decoration. In order to re-cut the relief designs, gravers and die-sinker chisels of various shapes are used. Squares, flats and several different radius bottomed tools. The process is very similar to carving in wood, only different material removal techniques must be used. After chiseling, some areas can be cleaned up with fine files and in other areas stones must be used. After stoning, loose pumice can be used as well as woven abrasives such as Scotch-Brite. Finally the entire piece is darkened with cold blue and then re-polished to darken low spots and accentuate the forms. The guard shown will be engraved with borders and perhaps some additional work on the grip rail and forward extension. As always, if there are any question or comments I'd love to hear from you. Thanks for all that have subscribed to follow these posts. Jim UPDATE: There have been a couple of questions that I'll talk about. The gray stuff shown in the above photo is a plastic that softens with temperature. It can be heated and formed around parts to hold them in place. In this case it's around the guard and a piece of wood clamped in the vise. For chisel work, it's important that the piece be held pretty solid. The little stones shown in the blog post are used quite a bit for polishing after chiseling. I bought mine from Congress Tools, though Geiswensells similar products. Some of my favorites are the "Y-oil", "regular" and "supersoft". I also have some brown ones with a reinforcing fiber that work well. Can't remember their name. They sell some called "super ceramic" that I would like to try. I've heard very good things about them. The relief work on the Bongarde guard was not exactly what I wanted, so I decided to reshape things to some degree. The original decoration was rather weak in definition and I couldn't help but to get the feeling some of it might have been formed with forging dies.

|

AuthorJim Kibler--maker of flintlock rifles. Archives

May 2019

Categories

All

|

Kibler's Longrifles

HoursM-F: 8am - 6pm

|

Telephone |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed